Visual intelligence is arranging a set of facts on a page or screen so their implications are comprehensible instead of incomprehensible, and sorting and grouping can help a lot. A common example in published stats is the American states: there are fifty of them (plus the District of Columbia), and that's a lot to take in in one go, so some sorting would help.

Unfortunately the most common sorting for states is the notorious "Alabama first" system of simply listing them in alphabetical order. This might sound like a good idea if you haven't got a better one, but the question is, why haven't you got a better one? There's almost always a pattern you can use, and if there isn't you should seriously ask yourself why you're bothering with a graphic at all.

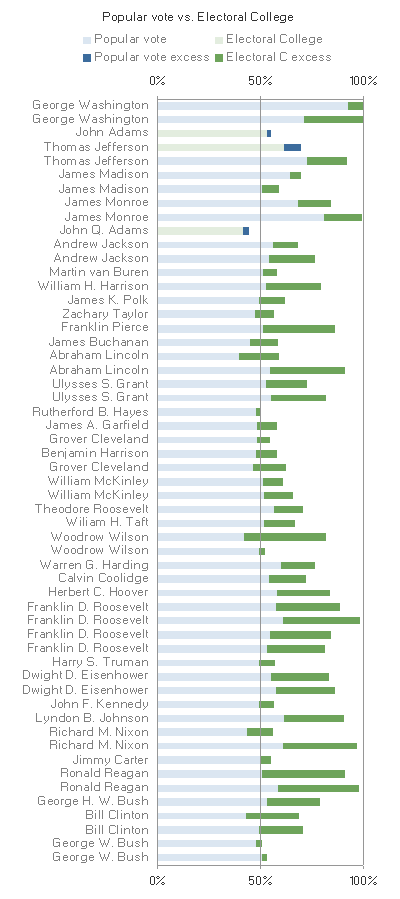

Consider this visual table (or reorderable matrix, as Bertin calls them) showing the state results of US presidential elections:

(you can click on all these tiny graphics to see a larger and I hope more readable version, though I'm trusting to Blogger's HTML settings on this occasion)

(you can click on all these tiny graphics to see a larger and I hope more readable version, though I'm trusting to Blogger's HTML settings on this occasion)You can vaguely see the ebb and flow of party wins over the whole country, but, sorted alphabetically by state abbreviation, this data set could be impossible to come to any more detailed conclusions about. But sort it by most recent results... ...and a pattern begins to emerge, showing which states have been most steady (at the left and right sides of their regional boxes) or most "swingy" (vacillating in the middle). Now group it (even if naively) into three regions and some things become even easier to see.

...and a pattern begins to emerge, showing which states have been most steady (at the left and right sides of their regional boxes) or most "swingy" (vacillating in the middle). Now group it (even if naively) into three regions and some things become even easier to see. Notice the switch over between north and south in the sixties.

Notice the switch over between north and south in the sixties.

Jorge Camoes has recently defended the pie chart, which has a bad reputation for looking like this:

He points out that with a bit of sorting and grouping, it can look more like this:

He points out that with a bit of sorting and grouping, it can look more like this: Actually, the first example was already sorted and grouped, but you wouldn't know it from the chaos of colours, which tells us that grouping is no good unless it's properly depicted, using colour fields, dividers, and group labels. By sorting and grouping, and showing the grouping, you can turn a large number of confusing values into something people can make sense of. I can't say it exactly makes me like pie charts, but it makes them less horrible.

Actually, the first example was already sorted and grouped, but you wouldn't know it from the chaos of colours, which tells us that grouping is no good unless it's properly depicted, using colour fields, dividers, and group labels. By sorting and grouping, and showing the grouping, you can turn a large number of confusing values into something people can make sense of. I can't say it exactly makes me like pie charts, but it makes them less horrible.